JLW Page, ‘An exploration of Dartmoor and its antiquities, with some account of its borders.’ (1889).

JLW Page, ‘An exploration of Dartmoor and its antiquities, with some account of its borders.’ (1889).

From ‘Dartmoor and its surroundings’ by B F Cresswell, 1900.

The Bowerman knows.

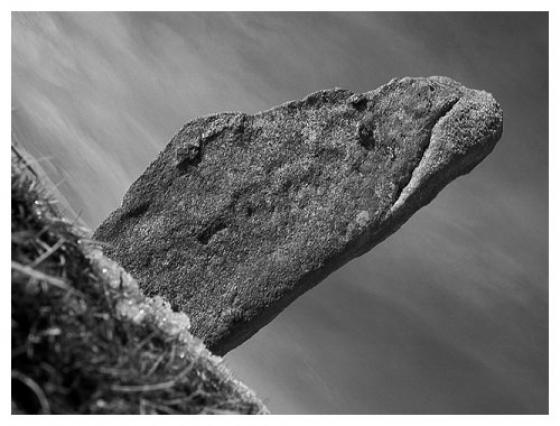

Bowerman’s nose.

Bowerman goes.

From higher up on the rocks.

20th July 2008

20th July 2008

20th July 2008

If you were to rub your scalp with one hand whist with the other rubbing the stones of Bowerman’s nose, and ask any question, in your next dream the answer will be revealed, because the Bowerman knows.

That’s not true, I made that up.

The rock stack is to me not very anthropomorphic, I struggle to see a nose, but the hat is quite clear. So if there is no nose, perhaps the rock had oracular powers. Disprove it.

Parking is scant but available for a few, a pleasant ten minute walk takes us up to the Granite god.

He is tall, perhaps he has a precise height, maybe not, he sits on the edge of a small platform at the bottom of an unnamed rocky Tor above Hayne down.

From up on top of the rocks you can see all the way to Hound Tor and the approximate location of the cairn with cist circle.

This is a very good place to get away from it all, but on a nice day like today, and presumably other days too, there will be other people, not many, but some.

The most popular bit of folklore surrounding Bowerman’s nose goes as follows. In the times of William the Conqueror a great Norman warrior (a Bow-man ) settled in the area. He was out hunting with his hounds one day when he he gave chase to a hare. The chase led the huntsman and his hounds crashing through a coven of witches who were about their work. The Huntsman scattered the coven and lost the hare.

The witches cooked up a scheme to revenge their dignity. Some time later Bowerman the bowman was hunting in the area once again when he spotted a pure white hare, a witch in disguise of course.

The witch led the hunter a merry chase until at the top of a hill on Hayne Down the witches sprang their ambush turning Bowerman into a pile of stones and his dogs into the rocks and clitter that surround him.

Now for a bit of amateur etymology. There are other places called “nose” on Dartmoor and it is clear that “nose” is being used as a generic term to describe an outcrop of rock. This meaning has become twisted in the case of Bowerman because in profile he looks very much like a face with a distinct nose. So Bowerman’s outcrop has become firmly fixed in modern imagination as Bowerman’s nose, wrongly drawing attention to one aspect of the rock pile rather than the whole site itself. So lets discount the nose and concentrate on Bowerman.

If there was a Norman noble Bowerman or Bowman living in the area he did not leave any traces of his name in the Doomesday book in 1086.

A more tempting theory is to be found if you look into the remnants of the celtic language where here in the far South West anything with Man, Men or Maen translates as “Stone” (in that way Cornwall’s famous Men an Tol becomes “Stone with Hole”). Given the word Vawr means “Great” then it is an easy step to see how Vawr Maen “Great Stone” becomes Bowerman.

I liked this theory right up to the point I was told that the Celtic/Cornish tongue would have put the words the other way round ie Maen Vawr.... “Stone Great” because the adjective comes after the noun. To prove the point there is a geological feature in Cornwall called Maen Vawr which over the years has transmogrified into “Man-O-War”. But how hard and fast is this adjective/noun rule ? Surely over millennia it could change... or is this just bending facts to fit a favourite theory?

Everyone is agreed that Bowerman/Bowman/Vawr Maen/ is a geological feature, but is it a sacred site ? At the foot of the rise on which Bowerman stands a prehistoric settlement has been found. Standing there at Blissmore you can appreciate Bowerman in all his glory, there has to be a link between Bowerman and those early settlers. Some people (including Mr Cope ) speculate that the ancients toppled similar rock piles nearby in order to leave Bowerman standing proud. The problem with that theory is when you consider the amount of effort put into toppling the other stacks, why did the architects then leave all the rubble lying around their new sacred site ?

Of course it is a lot of work to clear paths through the jumble of rocks, but that is exactly what has happened about 400 meters South of Bowerman where a 2 meter wide bronze age road picks its way through the granite slabs for about 200 meters. If they did it there, why not around the Idol?

My feeling is that Bowerman is a completely natural “found” holy place and landmark. The fact that the earliest oral traditions associate Bowerman with both witchcraft and a great Hunter figure also binds him closely in with the old religion. On a personal note, for me, Bowerman still has his mojo working. He dominates a fine a landscape and as you approach you know this is a sacred site. Just as some stone circles are said to defy attempts to count the number of stones in them so Bowerman has confused many visitors about his height. I have seen it recorded separately by well respected Dartmoor experts as 26 , 40 50 and even 55 feet. Go have a look for yourself !

[There is] the tradition that “Bowerman” lived in the locality at the time of the Conquest. He must have had something peculiarly striking in the pattern of his nose! Still we like to keep our “Bowerman” as a personality, and feel hardly grateful to modern learning, which comes down upon us with ponderous weight and says we have ignorantly corrupted the Celtic name of Vawr Maen, the Great Stone.

From ‘Dartmoor and its surroundings: what to see and how to find it.’ by Beatrix F Cresswell, 1900.

The stones of Hound’s Tor are meant to be the Bowerman’s hunting hounds.

The monumental mass of granite on Dartmoor, known as Bowerman’s Nose, may hand down to us the resting-place and name of a giant whose nose was the index of his vice; though Carrington, in his poem. of ” Dartmoor,” supposes these rocks to be

“A granite god,

To whom, in days long flown, the suppliant knee

In trembling homage bow’d.”

Let those, however, who are curious in this problem visit the granite idol; when, as Carrington assures us, he will find that the inhabitants of

“The hamlets near

Have legends rude connected with the spot

(Wild swept by every wind), on which he stands,

The Giant of the Moor.”

“Popular Romances of the West of England” Robert Hunt. 1903.