Wooded Aconbury (just right of centre) seen from Fishpool Hill to the east. The Black Mountains and Hay Bluff/Pen y Beacon can be see on the skyline beyond. Far right is another hillfort, Dinedor Camp.

Wooded Aconbury (just right of centre) seen from Fishpool Hill to the east. The Black Mountains and Hay Bluff/Pen y Beacon can be see on the skyline beyond. Far right is another hillfort, Dinedor Camp.

Further landscape context to show how visible Aconbury is from many directions. The hillfort is prominent on the skyline to the right of centre. Seen from Coppet Hill above Goodrich, some dozen miles to the south.

Aconbury rises prominently above its surroundings, centre. Seen from the road below Capler Camp to the northeast.

Landscape context of Herefordshire’s brilliant hillforts. Aconbury (left) and Dinedor Camp (right), with the Sugarloaf and Black Mountains beyond. Seen from another brilliant fort, Backbury, to the NE.

The wooded interior, from the southeastern (original) entrance.

The southeastern section of the rampart.

Come the summer much of the rampart will be obscured by vegetation.

The impressive but heavily overgrown southern rampart.

The southern rampart.

The southwestern corner of the fort. The encircling track moves away from the rampart here, so the original ditch can be seen at its best.

The western side of the fort.

The northwestern corner of the fort. The rampart survives to an impressive height, although the ditch has been filled in to create the track.

The eastern rampart.

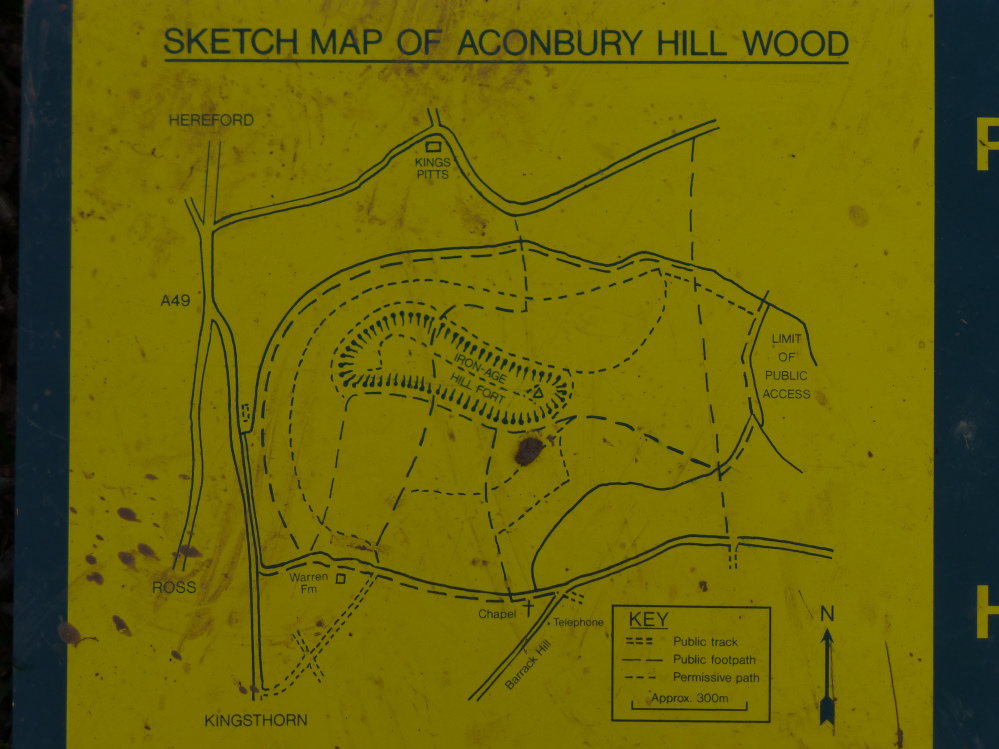

Plan of the fort, showing permissive access.

St Ann’s Well (see folklore) where my phone went temporarily dead.

St. Ann’s Pool (see folklore).

A visit was paid to St. Ann’s Well, and its pure waters were very refreshing. Its legend is lost, as is many another, from the much more frequent changes of abode by the agricultural labourers in these days.

Further up in the same field is the Lady Well; and here, said Mr. Lewis, a lady is said to have committed suicide. Nobody goes for its waters as they do to St. Ann’s, but happily the place seems not to be haunted.

Some more on the well(s):

“Washing in the waters of St Ann’s Well is said to cure various ills, particularly eye troubles. The first bucketful of water collected after Twelfth Night was supposed to be the best, and was considered worth competing for. It is said that the water in the pool [St Ann’s Pool, to the NE of the well] bubbles up at midnight on this day, and is seen to emit blue smoke. However, this is of course according to those who had gone there in the hope of curing their bad eyes.

Presumably before the calendar reform, this was a Yule custom, although New Year’s Day was the favoured time for collecting medicinal waters at Dinedor Cross and elsewhere.

At the top of the field is a scrubby piece of woodland containing the Lady Well, a holy spring which is haunted by the ghost of a young woman who killed herself there. In another more elaborate version of the story she killed her lover, wrongly suspecting him of infidelity, then died of heartbreak; as a result both spirits haunt the well where this happened and where they often meet.

There is a local memory that this well is dedicated to St Catherine. ‘Lady Well’ is a common name for a well and it naturally usually be assumed to be dedicated to St Mary, as for instance at Bodenham. But if the well was pre-Christian, the ‘Lady’ would simply have been the local goddess, who in this part of Herefordshire was more probably Christianised as St Catherine.”

From “The Healing Wells of Herefordshire” – Jonathan Sant (1994 Moondial) with reference to “The Folk-lore of Herefordshire” – Ella Mary Leather (1912).

This hill fort was inhabited from about 200BC to after the Romans arrived, though it seems that it’s known locally to be a ‘Roman Camp’.

On the NE side of the hill is a spring with certain magical powers, dedicated to St Ann. As usual it’s especially good for the eyes – but you had to collect the first bucket of water at the stroke of midnight on twelfth night, to ensure the best efficacy.

(Folklore of the Welsh Border, J Simpson 1976)

***

Caer Rhain is another name for Aconbury.

Baring-Gould suggests the Rhain of the name was Rhain Dremrudd, King of Brycheiniog. He translates ‘Dremrudd’ as red-eyed, but could it be more subtle than this? Trem is (I believe) Welsh for sight or gaze; could it not imply he got the red mist sometimes, rather than conjunctivitus. I dunno. Perhaps he should have visited the well (see above). All this etymology. It’s a minefield.

(Baring-Gould, ‘Lives of the British Saints’ v4, p 108. 1913)

From “The Beauties of England and Wales” Vol VI – Edward Wedlake Brayley and John Britton (1805):

“On the summit of Aconbury Hill, a bold and extensive eminence, partly covered with young wood, and commanding a delightful view over the adjacent country, are the traces of a large CAMP, of a square form: the rampart on the east side is very conspicuous. This was probably a summer camp of the Romans.”

The believed Roman-ness ties in with Rhiannon’s post about the local name being Roman Camp.

From “Herefordshire Record of Countryside Treasures” (1981 H&WCC):

“Aconbury Iron-age Camp

Single rampart surrounded by outer ditch, encloses 7ha. (17.5 acres) on N slope and summit of fort. Fort was used during the Civil Wars and probably modified then. Small piece of late Roman pottery found embedded in rampart, but site not excavated to date. There are two original entrances at SE and SW corners, the others being probably modern.”