Raising the fallen stone at Longstone Cove, Beckhampton, 1913. From photographs by Mr. Passmore and Captain Oakeley.

archive.org/stream/wiltshirearchaeo38wiltuoft#page/n13/mode/1up

Raising the fallen stone at Longstone Cove, Beckhampton, 1913. From photographs by Mr. Passmore and Captain Oakeley.

archive.org/stream/wiltshirearchaeo38wiltuoft#page/n13/mode/1up

Raising the fallen stone at Longstone Cove, Beckhampton, 1913. From photographs by Mr. Passmore and Captain Oakeley.

archive.org/stream/wiltshirearchaeo38wiltuoft#page/n13/mode/1up

This is really extremely unpleasant but I suppose it conceivably gives an insight into the way people saw this fort at the time – I have no proof but you would imagine the gibbet to be actually on or within its walls as it is the high point of the eponymous downs. It dimly brought to my mind the way Hardy uses Stonehenge as a wild no-man’s land for Tess of the D’urbervilles. As though it represented the opposite of somewhere civilised, somewhere apt for the end of someone uncivilised (not that anyone deserves such a way to go). Am I overanalysing, it is possible. It’s so horrible I wonder if I should post it, for potentially spoiling the atmosphere there for anyone that reads this and visits :)

“Anne, the daughter John Pollard, of this parish [St. Columb], and Loveday, the daughter of Thomas Rosebere, of the parish of Enoder, were buried on the 23rd day of June, 1671, who were both barbarously murdered the day before in the house of Capt’n Peter Pollard on the bridge, by one John the son of Humphrey and Cicely Trehembern, of this parish, about 11 of the clock in the forenoon upon a market day.”

The following tradition is given in connection with the above:= “A bloodhound was obtained and set upon the trail, which it followed up a narrow lane, to the east of the union-house, named Tremen’s-lane; at the head, the hound made in an oblique direction towards the town, and in a narrow alley, known as Wreford’s-row, it came upon the murderer in his father’s house, and licked his boots, which were covered in blood.”

The sentence on Tremen was “that he be confined in an iron cage on the Castle Downs, 2 miles from St. Columb, and starved to death.” While in confinement he was visited by a country woman on her way home from market. The prisoner begged earnestly for something to eat; the woman informed him that she had nothing in the shape of food but a pound of candles; this being given him, he ate them in a ravenous manner. It’s a saying here, in reference to a scapegrace, that he is a regular Tremen.

Richard Cornish. St. Columb.

From v1 of the Western Antiquary (June 1881).

This page has a photo of someone paying their rent onto the stone in the 1920s.

The cross mentioned by Gomme was originally near the boulder but it was moved to the vicar’s garden in the 1860s. In the 1980s it was moved back again.

In 1869 there was something more than a vague tradition that the manor courts were formerly held in the open air in a small open space or village green in the hamlet of Dunstone, and that the chief rents were deposited in a hollow or “rock basin” on the upper side of a huge granite boulder in the middle of the green, where a granite cross formerly stood. Mr Dymond resolved to revive the practice of the open-air court, and did so two years ago.

From Francis Gomme’s ‘Primitive Folk-Moots‘ (1880).

On the cliffs near this village is Bosigran Castle, a small promontory of bold granite rocks, across which the insignificant remains of a thick stone wall are believed by some to indicate that here is a specimen of one of the so-called cliff castles.

A large block of granite in the centre, covered at the top with rock-basons, is called the Castle Rock; and near this a large stone, scooped, as it were, through the top, is known as the Giant’s Cradle.

At the distance of a few yards from these, nearer the sea, is an excellent logan stone, a slab of granite over nine yards in circumference, with rock-basons on the top. A slight pressure upwards, or standing upon it, causes this rock to vibrate throughout its whole length.

From Rambles in Western Cornwall by the Footsteps of the Giants by J O Halliwell-Phillipps (1861).

I’m not sure why this stone hasn’t been added before. I think I always assumed it had gone long ago. But it’s on the MAGIC map when you zoom right in. In fact, on that map, it even calls it a ‘cup marked stone’. Someone must seek it out immediately and take a photo! It’s in the hamlet of Mayon, more than Sennen itself.

TABLE-MÊN.

The Saxon Kings’ Visit To The Land’s End.At a short distance from Sennen church, and near the end of a cottage, is a block of granite, nearly eight feet long, and about three high. This rock is known as the Table-mên, or Table-main, which appears to signify the stone-table. At Bosavern, in St Just, is a somewhat similar flat stone; and the same story attaches to each.

It is to the effect that some Saxon kings used the stone as a dining-table. The number has been variously stated; some traditions fixing on three kings, others on seven. Hals is far more explicit; for, as he says, on the authority of the chronicle of Samuel Daniell, they were --

Ethelbert, 5th king of Kent;

Cissa, 2d king of the South Saxons;

Kingills, 6th king of the West Saxons;

Sebert, 3d king of the East Saxons;

Ethelfred, 7th king of the Northumbers;

Penda, 5th king of the Mercians;

Sigebert, 5th king of the East Angles, -- who all flourished about the year 600.At a point where the four parishes of Zennor, Morvah, Gulval, and Madron meet, is a flat stone with a cross cut on it. The Saxon kings are also said to have dined on this.

The only tradition which is known amongst the peasantry of Sennen is, that Prince Arthur and the kings who aided him against the Danes, in the great battle fought near Vellan-Drucher, dined on the Table-mên, after which they defeated the Danes.

A bizarrely specific list from Robert Hunt’s ‘Popular Romances of the West of England‘, this edition from 1903. On page 306 he elaborates the battle, and adds the extra local details that King Arthur and the kings ‘pledged each other in the holy water from St Sennen’s Well, they returned thanks for their victory in St Sennen’s Chapel, and dined that day on the Table-men.’ Merlin was there too. Oh yes.

The stone’s mentioned in Bottrell’s ‘Traditions and Hearthside Stories of Western Cornwall‘ (1873) too. It mentions ‘Escols’ which is Escalls, which is within spitting distance, so perhaps the stones were used in the same way if they had the same title.

Within the memory of many persons now living, there was to be seen, in the town-places of many western villages, an unhewn table-like stone called the Garrack Zans. This stone was the usual meeting place of the villagers, and regarded by them as public property. Old residents in Escols have often told me of one which stood near the middle of that hamlet on an open space where a maypole was also erected. This Garrack Zans they described as nearly round, about three feet high, and nine in diameter, with a level top. A bonfire was made on it and danced around at Midsummer. When petty offences were committed by unknown persons, those who wished to prove their innocence, and to discover the guilty, were accustomed to light a furse-fire on the Garrack Zans; each person who assisted took a stick of fire from the pile, and those who could extinguish the fire in their sticks, by spitting on them, were deemed innocent; if the injured handed a fire-stick to any persons, who failed to do so, they were declared guilty.

Most evenings young persons, linked hand in hand, danced around the Garrack Zans, and many old folks passed round it nine times daily from some notion that it was lucky and good against witchcraft.

The stone now known as Table-mên was called the Garrack Zans by old people of Sennen.

If our traditions may be relied on, there was also in Treen a large one, around which a market was held in days of yore, as mentioned at page 77. There was a Garrack Zans in Sowah only a few years since, and one may still be seen in Roskestal, St. Levan.

Nothing seems to be known respecting their original use; yet the significant name, and a belief – held by old folks at least – that it is unlucky to remove them, denote that they were regarded as sacred objects. Venerated stones, known by the same name, were long preserved in other villages until removed by strange owners and occupiers, who are, for the most part, regardless of our ancient monuments.

At a point where the four parishes of Zennor, Morvah, Gulval, and Madron meet, is a flat stone with a cross cut on it. The Saxon kings are also said to have dined on this*.

*As well as at the Table-mên stone. See Popular Romances of the West of England, by Robert Hunt (3rd ed. 1908).

A man named Ronaldson, who lived in the village of Bowden, is reported to have had frequent encounters with the witches of that place. among these we find the following. One morning at sunrise, while he was tying his garter with one foot against a low dyke, he was startled by feeling something like a rope of straw passed between his legs, and himself borne swiftly away upon it to a small brook at the foot of the southernmost hill of Eildon. Hearing a hoarse smothered laugh, he perceived he was in the power of witches or sprites; and when he came to a ford called the Brig-o’-stanes, feeling his foot touch a large stone, he exclaimed, “I’ the name o’ the Lord, ye’se get me not farther!” At that moment he rope broke, the air rang as with the laughter of a thousand voices; and as he kept his footing on the stone he heard a muttered cry, “Ah we’ve lost the coof!”

From Notes on the folklore of the northern counties of England and the borders by William Henderson (1879).

Being from the south I didn’t know that ‘coof’ means “a dull spiritless fellow; one somewhat obtuse in sense and sensibility.” (could safely throw that in the conversation).

This is a bit vague. Perhaps the stone isn’t here any more. And even if it were, it’s surely a Disputed Antiquity. Apologies. I can see it marked on a map from 1890. The spring itself is still at the side of the Watergates Lonning track.

On the common, to the east of that village [Blencogo], not far from Ware-Brig (i.e. Waver Bridge) near a pretty large rock of granite, called St. Cuthbert’s Stane, is a fine copious spring of remarkably pure and sweet water; which (probably, from its having anciently been dedicated to the same St. Cuthbert) is called Helly-Well, i.e. Haly or Holy-Well. It formerly was the custom for the youth of all the neighbouring villages to assemble at this well, early in the afternoon of the second Sunday in May; and there to join in a variety of rural sports. It ws the Village Wake; and took place here, it is possible, when the keeping of wakes and fairs in the church-yard was discontinued. And it differed from the wakes of later times, chiefly in this, that though it was a meeting entirely devoted to festivity and mirth, no strong drink of any kind was ever seen there; nor any thing ever drank, but the beverage furnished by the naiad of the place. A curate of the parish, about twenty years ago, on the idea, that it was a profanation of the sabbath, saw fit to set his face against it; and having, deservedly, great influence in the parish, the meetings at Helly-Well have ever since been discontinued. We honour his zeal; but there are many principles and practices in the place, which we cannot but be sorry, he was not so successful in reforming, as he was in attacking this ancient, if not innocent custom; which would have been thought no abuse of the sabbath in most of the other countries of Christendom.

From The History of the county of Cumberland by William Hutchinson (1794).

From ‘Notes on the folk-lore of the northern counties of England and the borders’ by William Henderson (1879).

The following verse, though said to be popular in [nurseries in] Berwickshire, is unknown elsewhere:--

Rainbow, rainbow, haud awa’ hame,

A’ yer bairns are dead but ane,

And it lies sick at yon grey stane,

And will be dead ere you win hame.

Gang owre the Dramaw and yont the lea,

And down by the side o’ yonder sea;

Your bairn lies greeting like to dee,

And the big teardrop is in his e’e.The Drumaw is a high hill skirting the sea in the east of Berwickshire.

The New Statistical Account suggests Habchester is the place for this rather black rhyme.

There’s a nice aerial photo of the fort at Treasured Places, where you can see it crossed by a wall, one side ploughed down and the other still with its banks and ditches.

From John MacLean’s article in the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society for 1880-1.

archive.org/stream/transactionsbris05bris#page/n133

Even here, as well as in more extensive places, a monumental stone stands in the middle of a plain, ten feet high, and four broad, nearly of the same form with those so frequently met with elsewhere, and, like them also, there is no tradition whatever respecting either the time when, or the purpose for which it was erected. Around it, on the first day of the New Year, the inhabitants sometimes assemble for their amusement, and indulge for a while in the song and the dance.

From ‘History of the Orkney Islands‘ by Rev. Dr. George Barry (1808).

‘PAST’ newsletter 57 (from November 2007) has an article about excavations at Torbhlaren.

Not far from the house of Busta, is a large stone of granite, that appears as erect as if it had been fixed there by art. Not improbably it was a large boulder-stone, brought thither by natural causes, and placed in an upright position, as the memorial of some battle or death of a chief. It is supposed by the vulgar to have been thrown there by the Devil from some hill in Northmavine.

From ‘A description of the Shetland Islands‘ by Samuel Hibbert (1822).

There are several large mounds of this kind in the close vicinity of the Standing Stones of Stenness. In the latter part of the tenth century a party contest took place between two Jarls, Einar and Haarard, and their respective retainers, many of whom lie buried in these mounds. The spot on which they are situated used to be called Haarardshay, or the “field of Haarard.”

From Rambles in the Far North by R Menzies Fergusson (1884).

In the neighbouring parish of Birsay there is one of these Druidical stones, with a rather strange and tragic history attached to it. The legend runs that every Hogmanay night, as the clock strikes the hour of twelve, this stone begins to walk or move towards Birsay Loch. When the edge of the loch is reached it quietly dips its head into the rippling waters. Then, to remain firm and immovable until the next twelve months pass away, it as silently returns to its post.

It was never considered safe for any one to remain out of doors at midnight, and watch its movements upon Hogmanay. Many stories are current of curious persons who dared to watch the stone’s proceedings, and who the next morning were found lying corpses by its side.

The latest story of the kind is that of a young gentleman from Glasgow, who formed the resolve to remain up all night, and find out for himself the truth or falsehood about this wonderful stone. One Hogmanay accompanied only by the cold silvery beams of the moon, the daring youth began his watch. As time wore on and the dread hour of midnight approached, he began to feel some little terror in his heart, and an eerie feeling crept slowly over his limbs. At midnight he discovered that, in his pacing to and fro, he had come between the stone and the loch; and, as he looked towards the former he fancied that he saw it move. From that moment he lost all consciousness, and his friends found him in the grey dawn lying in a faint. By degrees he came to himself; but he could not satisfy enquirers whether the stone had really moved and knocked him down on its way, or whether his imagination had conjured up the assault.

There is another tale, of a more tragic nature, related of this walking stone. One stormy December day a vessel was shipwrecked upon the shore of Birsay, and all hands save one were lost. The rescued sailor happened to find refuge in a cottage close by this stone; and, hearing the story of its yearly march, he resolved to see for himself all that human eyes might be able to discover. In spite of all remonstrances, he sallied forth on the last night of the old year; and, to make doubly sure, he seated himself on the very pinnacle of the stone. There he awaited the events of the night. What these were no mortal man can tell; for the first morning of the new year dawned upon the corpse of the gallant sailor lad, and local report has it that the walking stone rolled over him as it proceeded to the loch.

From Rambles in the Far North by R Menzies Fergusson (1884). Loch of Birsay is an alternative name for Loch of Boardhouse.

The whole district of Plas is interesting, and must have been a place of importance in Celtic times. There are moreover still to be seen two large meinhirs of schist rock, measuring 11 ft. in height above the ground, and 10 ft. apart, which, as old tradition affirms, were surrounded by a circle of large stones, standing 4 or 5 ft. above the surface; many of these were removed by the tenants to build the outhouses, fences, and to form gate-posts. Almost all these stones are of trap rock, unhewn, each stone weighing four or five tons. There is one still standing in the field to the east of the two meinhirs above mentioned.

From an article about ‘Ancient Circular Habitations, Called Cyttiau’r Gwyddelod, at Ty Mawr in Holyhead Island; with Notices of Other Early Remains There.’ by the Hon. William Owen Stanley MP, in the Archaeological Journal for 1869 (v29)

From

archive.org/stream/archaeologicaljo26brit#page/310/mode/2up

volume 26 of the Archaeological Journal (1869).

I spent a very tranquil afternoon at Shapwick Heath today. It was so sunny, and when you’re wandering along the tracks in the dappled shade, dodging the soggiest peatiest spots, and being followed by dragonflies, it’s just marvellous. We sat in a hide for ages, looking out over one of the lakes, listening to the rustling reedbeds. It really is so quiet and remote feeling, you’ve got Glastonbury Tor poking up on the horizon, and you feel miles away from modern life. It’s very good for me. But to get to the point, at the moment, English Nature have opened the path that follows the line of the Sweet Track – it’s not always open as often it’s too wet. But at the moment you can walk through the wet woodland, brushing through all the sedges and the ferns (there are Osmunda royal ferns mmm) and walk pretty much where the builders of the track walked, back in 3800BC. How mad is that. It was a total pleasure. I recommend it very much.

There’s even a very decently surfaced path to where you can see (imagine) where the track was – EN take access pretty seriously at Shapwick. The other tracks around the reserve are variously accessible (most very much so), and of course they are all pretty flat, it being the Somerset levels. The specially-opened track does require you to climb up and down a few steps, wind along a narrow path, and hop across trainer-swallowing squishy peat though.

There’s some good information about the way the Sweet Track was built at Digital Digging. (And I finally discovered today that it’s called the ‘Sweet’ track because Mr Sweet was the man who spotted it. Just in case you were wondering too.)

Fairies at Almas, or Orms, Cliff, in Knaresborough Forest.

Almas Cliff is a prominent group of millstone grit rocks, said to have been sacred to the religion of the Druids, and still to retain many traces of the rites and observances of their faith. One rock is named the Altar Rock, and near to this is a natural opening in the cliff, about eighteen inches wide and five feet in height, which is known as the entrance to the ‘Fairy parlour.’ It is said to have been explored to the distance of one hundred yards, and to end in a beautiful room sacred to the ‘little people,’ a veritable fairy palace. Other reports say, that it is a subterranceous passage having an exit near Harewood Bridge – some two or three miles distant. This variation in report only shows how imperfect has been the exploration. It is to be doubted if any mortal has ever reached the fairy parlour. Some years ago, the story was related of daring explorers making the attempt, but so loud was the din, raised upon their advance, by rattling of pokers and shovels by the fairy inhabitants within, indignant at this invasion of the sanctity of their abode, that the too daring mortals precipitantly fled, by the way by which they had entered. Since then, no man seems to have dared the task of ascertaining the truth, as to this passage.

Grainge, the historian of Knaresborough Forest, says of the place: ‘It has always been associated with the fairy people, who were formerly believed to be all-powerful on this hill, and exhanged their imps for the children of the farmers around. With the exception of the entrance to the fairy parlour, all the openings, in the rocks, are carefully walled up to prevent foxes from earthing in the dens and caverns within; and the fairies, being either walled in, or finding themselves walled out, have left the country, as they have not been seen lately in the neighbourhood.‘

From Yorkshire Legends and Traditions by the Rev. Thomas Parkinson (1889).

Try not to swear while at Stony Raise.

In one of the narrow valleys here [in the neighbourhood of Lake Semerwater], there is a large cairn, or mound, or barrow, about one hundred yards in circumference, and called ‘Stone-raise,’ ‘Stan-raise,’ or ‘Stan-rise.‘

One legend states that a giant was once crossing the country here, with a huge chest of gold in his possession. Strong as he was, it required all his resolution to persevere in conveying it, as he did, upon his back, across these mountains and rugged dales. At last he came to where the mountain of Addleborough barred his way. He looked up, and, surveying it, swore that, in spite of God or man, he would bear his precious burden over its summit. No sooner had he spoken than the chest fell from his shoulders, and Stanrise sprung up and covered it. There the treasure remains. It will only be recovered, when some fortunate individual is able to secure the assistance of a hen, and an ape, to uncover it and draw it forth.

The other legend relates, that formerly a road ran past this place, from Bolton Castle over Greenborough Edge, to Skipton Castle in Craven. Along this road, a party of horsemen was passing from the one stronghold to the other, and, being met by wild and tempestuous weather, and becoming wearied, they dismounted, and rested themselves under the shadow of Stanraise. While thus resting, they swore that they would

‘From Bolton to Skipton Castle go,

Whether God would or no.‘

As a mark of the Divine displeasure at this profanity, the earth at the foot of the cairn opened, and swallowed up the whole party.

From Yorkshire Legends and Traditions by the Rev. Thomas Parkinson (1889).

There’s a remarkable amount of fairy folklore that goes with this area. You can’t help thinking that it’s connected with the remains of the prehistoric huts and fields that are here.

https://www.coflein.gov.uk/en/site/95402/

For example:

My next informant is Mr. Hugh Derfel Hughes, of Pendinas, Llangedai [..] Mr. Hughes says that he has lived about thirty-four years within a mile of the pool and farmhouse called Corwrion, and that he has refreshed his memory of the legend by questioning separately no less than three old people, who had been bred and born at or near that spot. [..]

“In old times, when the fairies showed themselves much oftener to men than they do now, they made their home in the bottomless pool of Corwrion*, in Upper Arllechwedd, in that wild portion of Gwynedd called Arvon. On fine mornings in the month of June these diminutive and nimble folk might be seen in a regular line vigorously engaged in mowing hay, with their cattle in herds busily grazing in the fields near Corwrion. This was a sight which often met the eyes of the people on the sides of the hills around, even on Sundays; but when they hurried down to them they found the fields empty, with the sham workmen and their cows gone, all gone. At other times they might be heard hammering away like miners, shovelling rubbish aside, or emptying their carts of stones. At times they took to singing all the night long, greatly to the delight of the people about, who dearly loved to hear them; and, besides singing so charmingly, they sometimes formed into companies for dancing, and their movements were marvellously graceful and attractive.

There’s a great deal more – it runs on for about 20 pages with numerous tales of fairy romance, fairy cattle, the power of iron, rumours of lost churches, ghosts, (and does mention the hut circles briefly).. it’s quite a place for such strangeness so it would seem. From Y Cymmrodor 1881, in a chapter on ‘Welsh Fairy Tales’ by Professor Rhys (doubtless John Rhys of ‘Celtic Folklore, Welsh and Manx’).

*now Cororion.

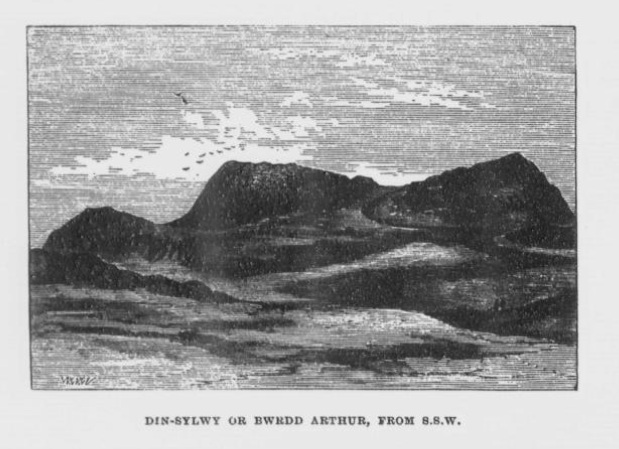

From W Wynn Williams’ article on Din Sylwy.

From W Wynn Williams’ article about Din Sylwy.

DINAS DINORWIG ROCKING-STONE.

To the Editor of the Arch. Camb.SIR,-- In the summer of 1863 I happened to be in the neighbourhood of Dinas Dinorwig, and, falling into conversation with one of the inhabitants, I was informed of a rocking-stone which stood a few score yards to the south-west of the camp. This stone I afterwards visited and found it to be a large boulder balanced upon a level rock, differing in no respect from the numerous blocks with which Carnarvonshire is studded, except in its massiveness and rocking quality. After several unsuccessful trials, with the assistance of a friend I succeeded in slightly moving the stone; but I was told that the children about could easily set it in motion. The truth of this information I could not test. Being lately in the same neighbourhood, I went out of my way to see the stone; but it had disappeared. Upon inquiry I ascertained that it had been blasted, and used in building cottages which stand within a stone’s throw of the site of the logan. It is a pity that this stone has been destroyed; for, whether mechanically poised, or left in its position by a melting glacier, it was not void of interest.

Dr. A. Wynn Williams, in his pamphlet on Arthur’s Well, thus alludes to the rocking-stone: “At the foot of the Dinas, on the western side, in a field called ‘Cae Go’uchaf’ (or the highest blacksmith’s field), on Glasgoed Farm, near the Groeslon, or crossing, close to the road, are some old ruins, probably Druidical. Amongst them is a very large rocking-stone. The circumference of the stone measures in length 24 feet; in width, 16 feet. It might weigh from ten to fifteen tons. A child of seven or eight years of age can move it with ease. I am not aware that this remarkable stone has ever been noticed in any antiquarian work; which is rather curious, as these things are not common in this neighbourhood or country.”

Yours respectfully, E.O.

From ‘Archaeologia Cambrensis v13 (October 1867).

From ‘English Forests and Forest Trees’ (1853)

archive.org/stream/englishforestsa00unkngoog#page/n208/

“Le Creux es Faies.”

This Cromlech is situated on the Houmet Nicolle at the point of L’Eree, (so called from the branch of the sea, Eire, which separates it from the islet of Notre Dame de Lihou). This island, which once had upon it a chapel and a priory dedicated to “Notre Dame de la Roche,” was always considered so sacred a spot that even to-day the fishermen salute it in passing... [The cromlech] is, as its name would lead one to suppose, a favourite haunt of the fairies, or perhaps, to speak more correctly, their usual dwelling place.

It is related that a man who happened to be lying on the grass near it, heard a voice within calling out: ”La paille, la paille, le fouar est caud.” (The shovel, the oven is hot). To which the answer was immediately returned: ”Bon! J’airon de la gache bientot.” (Good! We shall have some cake presently).

Another version from Mrs. Savidan is that some men were ploughing in a field belonging to Mr. Le Cheminant, just below the Cromlech, when the voice was heard saying ”La paille,” etc. One of them answered, ”Bon! J’airon de la gache,” and almost immediately afterwards a cake, quite hot, fell into one of the furrows. One of the men immediately ran forward and seized it, exclaiming that he would have a piece to take home to his wife, but on stooping to take it up he received such a buffet on the head as stretched him at full length on the ground. It is from here that the fairies issue on the night of the full moon to dance on Mont Saint till daybreak.

This is still believed, for in 1896, when my aunt, Mrs. Curtis, bought some land on Mont Saint, and built a house there, the country people told her that it was very unlucky to go there and disturb the fairy people in the spot where they dance.

My cousin, Miss Le Pelley, writes in 1896 from St. Pierre-du-Bois, saying “The people still believe the Creux des Fees and ‘Le Trepied’ to have been the fairies’ houses, and as proof one woman told me that when they dug down they found all kinds of pots and pans and china things.

From Guernsey Folklore by Edgar MacCulloch (1903).

Much information about Guernsey sites. You can contribute your own photos and comments.

My favourite type of folklore – rock art folklore. Or at least, I think it’s a fair guess to say that’s what this story refers to.

The Hoof-prints of Scota’s Steed at Ardifour Point.

At the mouth of Loch Craignish, but on the Kilmartin side of the loch, is the farm of Ardifour. One side of this farm faces Loch Craignish, and another Loch Crinan. Between the two lochs is a point where there are deep indentations in the rock, which bear some remote resemblance to the hoof-prints of a horse. How were these formed? A geologist could easily answer the question; but legend also has its own way of solving the difficulty.

Scota, the daughter of Pharoah, King of Egypt, came over from Ireland, and having entered the mouth of Loch Crinan, drew up her ship opposite Ardifour Point. She then mounted her steed, shook the reins, and thus urged the high-mettled animal to spring from the deck on to the distant point; and so violent was the shock that the hoofs of the horse sank deeply into the rock, and left behind them those marks which are still to be seen at Ardifour.

From ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’ (Argyllshire series) by Archibald Campbell (1889).

Rock art UK’s photo here isn’t totally unlike four hoofmarks?

Cader Ellyll means Elf’s Chair.

I take it you didn’t see any elves or you probably would have mentioned it.

Mid Argyll: a field survey of the historic and prehistoric monuments – by Marion Campbell and Mary L S Sandeman.

This article is cited frequently in the Canmore records for the area, and was printed in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland v 95 (1961/2).

There’s a natural knoll not far from the Barbreck stones. A mausoleum was built here in the late 18th century, and the builders found a cist made of four large stones and a gabled capstone. Inside was an urn and cremated remains. There’s an upright slab on the side of the knoll too.

Canmore record

The Battle between the Craignish People and the Lochluinnich Norwegians at Slugan.

The Norwegians once made a sudden descent from their ships on the lower end of Craignish. The inhabitants, taken by surprise, fled in terror to the upper end of the district, and halted not until they reached the Slugan (gorge) of Gleann-Domhuinn, or the Deep Glen. There, however, they rallied under a brave young man, who threw himself at their head, and slew, either with a spear or an arrow, the leader of the invaders. This inspired the Craignish men with such courage that they soon drove back their disheartened enemies across Barbreck river. The latter, in retreating, carried off the body of their fallen leader, and buried it afterwards on a place on Barbreck farm, which is still called Dunan-Amhlaidh, or Olav’s Mound. The Craignish men also raised a stone at Slugan to mark the spot where Olav fell.

From ‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’ (Argyllshire series) by Archibald Campbell (1889).

Slugan is now Sluggan on the OS map.

This ruined dun’s name means ‘Castle of the Black Dogs’.

From‘Waifs and Strays of Celtic Tradition’ (Argyllshire series) by Archibald Campbell (1889).

The Fight between Bran and Foir or For.

The black dog, Foir, was the brother of Bran, the far-famed hound of Fionn. Foir was taken early from his dam, and was afterwards nurtured by a band of fair women, who acted as his nurses. He grew up into a handsome hound, which had no equal, in the chase or in fight, in the distant North. His owner, Eubhan Oisein, the black-haired, red-cheeked, fair-skinned young Prince of Innis Torc (Orkney ?) was proud, as well he might be, of his unrivalled hound. Having no further victories to win in the North, his master determined to try him against the strongest dogs in the packs of the Feinne.He left home, descended by Lochawe, and entered Craignish through Glen Doan. Before his arrival, the Fienne, after spending the day in the chase, encamped for the night in the upper end of Craignish. Next day Fionn arose before sunrise, and saw a young man, wrapped in a red mantle and leading a black dog, approaching towards him at a rapid pace. The stranger soon drew near, and at once declared his object in coming. He wanted a dog-fight, and so impatient was he to have it, and so restless by reason of his impatience, that he suffered not his shadow to dwell a moment on one spot.

Fifty of the best hounds of the Feinne were slipped at last, but the black dog killed them all one by one. A second and then a third fifty were uncoupled, but the strange dog disposed of them as easily as he did of the first.

Fionn now saw that all the dogs of the Feinne were in serious danger of being annihilated, and therefore he turned round and cast an angry look on his own great dog Bran. In a moment Bran’s hair stood on end, his eyes darted fire, and he leaped the full length of his golden chain in his eagerness for the fight. But something else besides the casting of an angry look was still to be done to rouse the fierce hound’s temper to its highest pitch.

He was placed nose to nose with his rival, and then his golden chain was unclasped. The two hounds, brothers by blood, but now champions on opposite sides, at once closed in deadly fight; but for an adequate description of the struggle between them the reader must consult the bards. See the “Lay of the Black Dog”, in Islay’s Leabhar na Feinne, the McCallum’s Ancient Poetry, etc.

The contest lasted from morning to evening, and victory remained, almost to the close, uncertain; but in the end Bran vanquished Foir, and, by killing the latter, amply revenged the death of the three fifties. The Feinne buried their own dogs, and the stranger, with a sore heart, laid his black hound in the narrow clay bed.

This great dog-fight, so celebrated in Gaelic lore, is said to have been fought at Lergychony, in Craignish. It is further said that the place was called Learg-a-choinnimh, or the “Plateau of Meeting”, because it was there the two hounds met in fight. There are, of course, many other places in the Highlands which claim the honour of being the scene of this legendary contest.

The bit above where the author suggests you should find the exciting bit yourself has the same effect as an ad break in the middle of a film. The song is also called “Laoidh a’ Choin Duibh” but I’ve not spotted a translation yet.

And Foir’s upbringing sounds highly irregular, does it not almost sound as though he was wet-nursed by human beings? Maybe a bit of that Celtic style supernatural fuzzying of the natural and human worlds?

I thought there might be mounds round here for the burying of the 150 poor dogs, or maybe the dun’s mound is it. But there is also supposed to be a standing stone to commemorate Foir at

NM 8013 0773. The Canmore note is unimpressed, but it is very nearby and a not insubstantial 8’10” by 2’5” by 2’2” (reclining – there’s a photo on the MP https://46.37.163.74/article.php?sid=27532).

https://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/22731

From the Google Books image linked to below. You can’t help thinking that the person who did the etching hadn’t been there and was trying in vain to decipher someone else’s drawing.

About a mile south of the bridge over the Earn at Comrie, on the moor of Dalginross, and on the left side of the road going to Glenartney and Braco, there is a well-known standing stone, popularly named after Samson.

It is one of a group of three. The other two are lying to the east, and on the upper side of the eastmost one, there are twenty-six cup marks.

From ‘Notes on Cup-Marked Stones, Old Burying -Grounds, and Curing or Charm Stone, near St. Fillans, Perthshire’ by J M Gow – Archaeological Review October 1888.

On a swampy common called Saltonstall-moor, in Warley, is a fine large altar, called by the country people the Rocking Stone, the height of which on the West side, is about three yards and an half. It is a huge piece of rock, with rock basins cut upon it, one end of which rests on several stones, between two of which is a pebble of a different grit, seemingly put there for a support, and so placed that it could not possibly be taken out without breaking, or removing the rocks; these in all probability have been laid together by art. The stone in question, from the form and position of it, could never be a rocking stone, though it has always been distinguished by that name: the true rocking stone lies at a short distance from it, thrown from its centre. The other part of this stone is laid upon a kind of pedestal, broad at the bottom, but narrow in the middle; and round this pedestal is a passage, which from every appearance, seems to have been formed by art, but for what purpose is uncertain.

He conjectures that people passing through such passages would have acquired some kind of holiness, or knowledge, or that it was a sort of rite of passage. That sort of thing.

At the distance of about half a mile from this huge rock are the remains of a Carne, formed of loose stones, which for centuries has been called by the country people, Sleepy Low. Several broken fragments of rock are strewed over the moor, these are rendered more remarkable from the fact that the common is one vast morass.

From ‘A concise history of the parish and vicarage of Halifax’ by John Crabtree (1836).

From the Rev. Baring-Gould’s ‘Lives of the British Saints’, v1, 1907.

archive.org/stream/livesofbritishsa02bariuoft#page/96/mode/1up

In the interests of possibly outcroppy places with stoney folklore I am compelled to add this curious feature. (No, I do admit I’ve no proof it has prechristian significance.) Someone went to a lot of effort to turn this boulder into a not terribly comfy-looking chair, and it must have been done some time ago as it was apparently mentioned in a 15th century poem by Hywel Rheinallt. I can’t find anything about it online and still less a photo, but it’s on modern maps and I think I can even see it on satellite photos.

The writer in the 1856 ‘Archaeologia Cambrensis‘ says:

On a small eminence, a quarter of a mile eastward from the church, is a large boulder stone, with a flat piece cut out of it, called Cadair Cawrdaf, -- St. Cawrdaf’s Chair, from time immemorial. Judging from the site, the saint must have been a lover of the picturesque, for the view is one of extreme beauty and extent.

The church in Abererch is dedicated to Saint Cawrdaf, and not far away northwest, at SH38823735, is his spring, Ffynnon Cawrdaf.

Interpretation panels and information from the Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust.

Not far from this church there is, at Cefnbrallan, a huge ruined cromlech, with its cap overturned and broken; one of the upright stones measures 64 inches in height. Whilst this was being sketched a peasant was interrogated as to its partial destruction; he could not tell us when the damage was done, but he told us in Welsh that some fifty years ago an attempt was made to further destroy the cromlech, when a dreadful storm overtook and stopped the evil worker in his misdeeds. Our informant said, that whilst the sudden storm thundered overhead, the earth shook and trembled beneath, and all the time these great and mysterious stones remained immovable.

From ‘The Gardeners’ Chronicle‘, Sept 1875.

This relic is a rude stone, forming a kind of chair, lying in a field adjoining the churchyard, and about thirty or forty yards from it. When it was removed to its present position is unknown. There was also a well below the church called Ffynnon Canna; and there is still a small brook available, if required, for following the rules prescribed to those who wish to avail themselves of the curative powers of the saint’s chair. It appears that the principal maladies which are thus supposed to be cured are ague and intestinal complaints. The prescribed practice was as follows.

The patient first threw some pins into the well, a common practice in many other parts of Wales, where wells are still thought to be invested with certain powers. Then he drank a fixed quantity of the water, and sometimes bathed in the well, for the bath was not always resorted to. The third step was to sit down in the chair for a certain length of time; and if the patient could manage to sleep under these circumstances, the curative effects of the operation were considerably increased. This process was continued for some days, even for a fortnight or longer. A man aged seventy-eight, still living near the spot, remembers the well and hundreds of pins in it, as well as patients undergoing the treatment; but, about thirty or thirty-five years ago, the tenant carried off the soil between the well and the watercourse, so as to make the spring level with the well, which soon after partly disappeared, and from that time the medical reputation of the saint and her chair has gradually faded away, and will, in the course of a generation or two, be altogether forgotten.

There can be little doubt that the present church occupies the site of the old and original building of Canna, although there is, in the middle of the parish, a field called Parc y Fonwent, or the churchyard field, where, according to local tradition, the church was to have been originally built, but the stones brought to the spot during the day, were removed by invisible hands to the spot where the present church now stands, accompanied by a voice clearly pronouncing this sentence: “Llangan, dyma’r fan,” or, “Llangan, here is the spot.” Such miraculous removals of stones are reported and believed in many other parts of Wales; and in the present instance the story seems to have arisen from the circumstance of the field in question having been formerly church property.

More (on the inscription) here in Archaeologia Cambrensis (1875) and here.

Coflein puts the stone at SN17701874 and says before 1925 it used to be here SN17751875. But how big is it? You’d think it was too big to move. And (my ultimate excuse for including this stone) surely it was around here near the spring and the special insisted-upon spot before the church turned up. (Perhaps it’s smaller than I hope, as the RCAHMW puts it at 28 by 26 inches).

I can’t find a photo (and I think Ocifant’s tried to find the place in person without luck?) but the drawing in ‘Lives of the British Saints’ shows the slightly ambiguous lettering and the hollow “produced by the multitude and frequency of the devotees”.

The four remaining kings in more closely-grazed times.

From the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle:

archive.org/stream/newcastleser308sociuoft#page/246

“It is said respecting these, that the whole countryside around here belonged to five brothers who were five kings, and these stones were erected to their memory. I have been told that when the late Dr. Bruce* approached the ‘Five Kings’ he reverently uncovered his head.”

*John Collingwood Bruce – R*man wall expert.

Trough On Harehope Moor, Northumberland.

Mr S. Holmes (treas. and a vice-pres.) read the following notes:-

“On a recent visit to Eglingham I was shown a tank cut out of a mass of sandstone rock projecting in a curved form from the peaty surface. The rock is situated on the moor a short distance above the farm buildings of Harehope, and the trough or tank cut into it occupies a considerable proportion of the exposed rock. It is 7 ft. long and 5 ft. wide at the higher end, 4 ft. 6 in. wide at the lower, with depths ranging from 2 ft. to 2 ft. 3 in., and the floor rises from the outlet about 9 in. to the high end, thus giving a gradient of about 1 in 10. The sides and bottom are cut with the skill of a quarryman. And at the lower end the rock has been cut away on the outside so as to leave only a thin plate like the end of an ordinary trough which has a drainage hole cut through it, and there is no provision for inflow or of overflow.

Altogether the excavation has a modern appearance, but there are on each side of it what appears to be work of pre-historic date, viz.:- two small circular cup markings having roughly chased channels from them. The western one ending in a cross marking like a shark’s tail, but owing to the overgrowth of turf I was unable to follow the eastern one to its termination.

There is also a neatly cut bevelled hole on the west side of the trough, about two inches square. It is difficult to imagine what might have been the original purpose of the tank. Local tradition assigns it to the preparation of wine from the juniper berries, but seeing that the cubic contents, after allowing for the rise of floor, would have been about 500 gallons, it is difficult to think that ‘schnaps’ upon so large a scale would have been manufactured there.

Other theories about the tank incorporate the medieval hospital for lepers that was nearby. The pastscape record for the hospital says “the cistern is situated between the 500’ and 600’ contour on the E side of Harehope Hill and 1/4 mile NW of the farmhouse.” It sounds interesting but I wonder what Knowledgeable Opinion has to say on the rock art. Maybe the carvings aren’t exciting enough for the Beckensall archive as I couldn’t find them on there, or maybe they’ve been discounted?

From the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, vol 9, 1899.

There’s a photo here:

https://www.panoramio.com/photo/24466887#comment

and this one

https://www.panoramio.com/photo/24467027

would suggest the carvings on the outcrop had a super view before someone stuck a hole through them :)

From ‘Handbook to Cardiff’.

archive.org/stream/handbooktocardif00brit#page/n9/mode/2up

There is a well on this mount which was in former days named “Giant’s” Well, on account of the giant Cormelian, or Cormoran, who inhabited the spot. The well, or cistern, is excavated in the rock; it is still in existence, but is now known by the title of “Jack the Giant Killer’s Well,” and is fairly well lined with pins thrown there by persons desirous of procuring their wishes. The conclusion to be drawn is that the clever youth “Jack,” who by stratagem ridded the mount of its monster by killing the giant Cormoran, was honoured by the change of the well’s designation as a recognition of his service.

From ‘Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall’ by M and L Quiller-Couch (1894).

“This famous well is in the parish of Sancreed, not far from the Land’s End. The water wells forth, but the building which once covered it is demolished. Dr Borlase says (Nat. Hist. of Cornwall, p.31. Date AD 1757) that ‘as a witness of its having done remarkable cures, it has a chapel adjoining to it, dedicated to St. Eunius, the ruins of which, consisting of much carved stone, bespeak it to have been formerly of no little note. The water has the reputation of drying humours as well as healing wounds.‘

He adds that, ‘the common people (of this as well as other countries) will not be content to attribute the benefit they receive to ordinary means; there must be something marvellous in all their cures. I happened, luckily, to be at this well upon the last day of the year, on which, according to vulgar opinion, it exerts its principal and most salutary powers. Two women were here who came from a neighbouring parish, and were busily employed in bathing a child. They both assured me that people who had a mind to receive any benefit from St. Euny’s well, must come and wash upon the first three Wednesdays in May. But to leave folly to its own delusion, it is certainly very gracious in Providence to distribute a remedy for so many disorders in a quality so universally found as cold is in every unmixed well water.‘

Dr. Paris describes it as it was some sixty years ago. The ruins of a chapel or baptistery were observable near, and the water of the well was then supposed to posess many miraculous virtues, especially in infantile mesenteric disease. They were dipped on the three first Wednesdays in May, and drawn through the pool three times against the sun and three times on the surrounding grass in the same direction. (Guide to Mount’s Bay, etc. p.82).

This well, according to this distinguished physician and chemist, like Madron, does not contain any mineral impregnation, but must derive its force and virtue from the tonic effects of cold, and from the firm faith of the devotees. The credulous still go here to devine the future in the appearance of the bubbles which a pin or pebble sends up.

‘Two or three carved stones are all that remain of the old structure; and at the stated times when the well is sought for divination and cure, a bath is formed by impounding the water by turves cut from the surrounding moor. The country people know it as the Giant’s Well.’ -- T.Q.C.

Now it is simply an open spring, all remains of the building are gone, and the site obliterated. The water is not used for any special purpose, and the well is only remembered for its past importance.

From ‘Ancient and Holy Wells of Cornwall’ by M and L Quiller-Couch (1894).