Map of the complex, the tombs I-III are right next to each other and form what seems to be a single huge long barrow

Visited May 2019

Horneburg 2 is an approximately northeast-southwest oriented long barrow of about 80 meters in length. From the enclosure only a few stones on the southeastern long side are preserved. Approximately in the middle is a no longer complete chamber. It is believed that it originally consisted of 4 yokes. At the western end of the long barrrow is a second, also heavily destroyed chamber.

On the current map of the necropolis Daudieck the site is designated as station 4.

Visited May 2019

Horneburg 3 is located about 125 m south of Horneburg 2 in the western corner of a wooded area. The site is oriented almost in east-west direction. It is a very heavily destroyed long barrow. Visible is still a 48 meters long and 6 meters wide hill. In the middle lies the rest of a chamber. Visible are still three supporting stones. From the enclosure only two stones are preserved.

Along with Horneburg 3 this tomb is station 6 on the current map of the necropolis Daudieck walk.

Visited May 2019

Immediately to the east of Horneburg 3 lies the passage grave Horneburg 4. The enclosure of the approximately 39 m long barrow is almost not preserved, except for three stones south of the chamber and west of the entrance. However, the chamber is completely preserved except for the capstones. Only the western capstone is still on the support stones, the other two are missing. The still available entrance to the chamber is located on the south side and still has a capstone.

Along with Horneburg 3 this tomb is station 6 on the current map of the necropolis Daudieck walk.

Visited May 2019

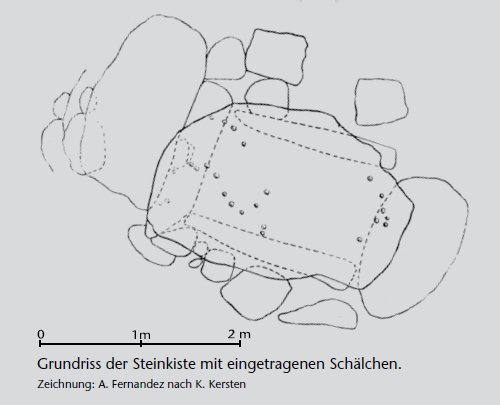

About 220 m southwest of Horneburg 3 and Horneburg 4 lies a striking mound under a group of trees in the field. In the mound in a hollow is a stone cist, from which a 2 meter large capstone can be seen. The support stones of the chamber are not exposed. The capstone has a number of cup marks.

On the current map of the necropolis Daudieck the site is designated as station 7.

Visited May 2019

taken from the information board of station 6:

Megalithic tombs in the long barrows B and C

The process for the construction of the megalithic tombs was tried by replicas to get on the track. Without major problems, the method proved first to raise a smaller hill. In it the support stones can be brought into position. The empty space is filled and a ramp heaped up to the top of the support stones. Over the slope, the capstones are pulled to their destination and fitted. Thereafter, the chamber can be freed from soil again and the “interior work” begins.

The gaps between the irregularly shaped support bricks are dry-walled with layers of shallow-cut smaller stones. Different materials were used for the chamber bottoms: field stones set in paving, stone gravel in loam, pure loam and others. Divided into the ground were more frequent divisions, for example – as here in the chamber of long barrow B – rows of stones, the “quarters / districts” separated from each other. Presumably these were markings, which deceased could be buried where. The renovation of the mound and the grounds will be the last construction work. The lockable passage made it possible to re-enter the chamber as often as required. Not only the builders of the tombs used this fesature, but also the following population, which were not the funnel beaker people. Around 2500 BC, a society immigrated to this region, whose livelihood as a shepherd was the cattle.

In addition to their own funeral rites, which they call “single grave people”, they also cleared the bones of funnel beaker people from the chambers and used some of their own deceased. Therefore undisturbed funnel beaker burials are rather rarely in the stone chambers. Only a remnant of the supporting part of the earlier elaborate burial grounds has come over as ruins.

taken from the information board of station 6:

Megalithic tombs in the long barrows B and C

The process for the construction of the megalithic tombs was tried by replicas to get on the track. Without major problems, the method proved first to raise a smaller hill. In it the support stones can be brought into position. The empty space is filled and a ramp heaped up to the top of the support stones. Over the slope, the capstones are pulled to their destination and fitted. Thereafter, the chamber can be freed from soil again and the “interior work” begins.

The gaps between the irregularly shaped support bricks are dry-walled with layers of shallow-cut smaller stones. Different materials were used for the chamber bottoms: field stones set in paving, stone gravel in loam, pure loam and others. Divided into the ground were more frequent divisions, for example – as here in the chamber of long barrow B – rows of stones, the “quarters / districts” separated from each other. Presumably these were markings, which deceased could be buried where. The renovation of the mound and the grounds will be the last construction work. The lockable passage made it possible to re-enter the chamber as often as required. Not only the builders of the tombs used this fesature, but also the following population, which were not the funnel beaker people. Around 2500 BC, a society immigrated to this region, whose livelihood as a shepherd was the cattle.

In addition to their own funeral rites, which they call “single grave people”, they also cleared the bones of funnel beaker people from the chambers and used some of their own deceased. Therefore undisturbed funnel beaker burials are rather rarely in the stone chambers. Only a remnant of the supporting part of the earlier elaborate burial grounds has come over as ruins.

Between Issendorf and Gut Daudieck is the “city of the deceased”, the necropolis Daudieck. Easily accessible during a walk, numerous tombs of several millennia lie on the flat slope down to the river Aue. The oldest tombs are the largest and the most elaborate: in the period from about 5,000 to 4,500 years ago, some buried their deceased in megalithic tombs. The circular walk is archaeologically extremely exciting and is about 2 kilometers long. Along the route there are a total of nine stations, several burial mounds (stations 2, 5, 8 and 9) three megalithic tombs (station 4 and 6) and a stone cist (station 7).

Visited May 2019

taken from the information board of station 4:

Megalithic tombs in long barrow A

During the cultural-historical period, called the Neolithic period (about 4000 to 2000 BC), there was a period of two different burial customs: tombs, which are very similar to today’s coffin burials, and closed burial chambers. In this area large boulders were available as building material, which were still lying around in large numbers on the ground surface 5000 years ago. They come, as all the soil in northern Germany, from Scandinavia and were during the penultimate Ice Age (about 250,000 to 130,000

years) transported here. The people who built megalithic tombs introduced agriculture to our area. They were the first with a sedentary lifestyle. Also they produced a considerable number of ceramic vessels. After a characteristic pot shape they produced, we call them funnel beaker people.

Usally, only a stone chamber is under an elongated hill (long bed) or in a round hill. In this long bed are two chambers. From the archive of the Daudieck estate we know that by 1780 more than 100 kerbstones of the ??the mound enclosure were present. In addition to the few support stone of the chamber only eleven of them have survived. The width of the chambers depends on the largest available boulders, which could be moved as capstones. The length is not subject to such constraints, because in each case a capstone on two opposite support stones – forming a so-called yoke – could be placed in any number together. In fact, the number of yokes used is determined by the offer of stone and the local building tradition. In the Weser-Ems area for example, up to 13 yoke long tombs were built.

taken from the information board of station 5:

Central burials in burial mounds

During the centuries from about 1500 to 1200 BC the dead were often laid in halved, hollowed out tree trunks, covered with wooden planks, and then a large mound was heaped up. The tree-coffins lay on field stone paving. Wedge stones came in the gusset between stones and trunk, so that it lay stable. On the soil freed from the topsoil, this arrangement gave an excellent rest. Why in later times cremation was the usual kind of burial is one of the interesting questions in our cultural history. Archaeological excavations have revealed, among other things, that during the earliest incinerations stone pavement and halved tree trunk were maintained. So there was an urn with the burnt ash in the coffin. The next step was to put the urn directly on a pavement, until one later renounced even the stone setting.

taken from the information panel of station 2:

Burial mounds

Burial mounds, which were built between about 1600 and 1200 BC, with diameters of 15 m to 20 m at a height over 3 m are not a rarity. Only a fraction of the original site are preserved. Most of them are not complete anymore. As with this mound almost always missing is the enclosure of large field stones or organic building material such as wooden posts or wicker, which can still be traced at the mound foot. Already during the Bronze Age around 1500 BC when the construction of burial mounds was custom, there must have been large heathland, because many mounds have been piled up with heath sods. Because heather, however, only occurs in a cultural landscape, we can conclude that humans have used large areas of land and brownfields already 3400 years ago.

taken from the information board of station 9:

Grave robbers

Plundering of the burial mounds was early on. Objects such as daggers, swords, arm and leg jewelry could have been reused after the robbery. However, no objects from the burial mound time in later centuries are archaeologically documented. Rather, the bronzes was melted again to re-produce the currently used things. Bronze as a raw material had to be always imported in this area, which is why it had a high value. Other grave robbers also used the mounds to extract raw materials: sand and stones are still mined and otherwise reused. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was an antiquarian interest in teachers and pastors who dug into the mound from above to retrieve the grave goods of the central burial. “Old pots”, when found, usually were left broken in the overburden.

taken from the information board of station 7:

Stone cist in the burial mound

Burial mounds with stone “cists” for the central tomb were rarer than tree-coffins. This type of funerals were probably at the beginning of the burial mound time the prefered manner. The principle is to build a stable, maybe permanent protection for the burial. 1000 years later, from 600 BC, urns were also places in stone boxes. The stone cist of this mound holds a special feature: located on the capstone are cup marks (bowls). Cup-marked stones can also be found at other places, but usually not as part of a tomb, but in its own function. Unfortunately, a convincing reason why there are cups drilled or pecked into the hard boulders are not found yet. Most assumptions refer to cultic actions.

The stone cist lies under this group of trees

Visited May 2019

The capstone contains several cup marks

Visited May 2019